Robert W. Paul’s early innovations helped catapult British film onto the world stage. He was one of the first filmmakers to add narrative to his movies.

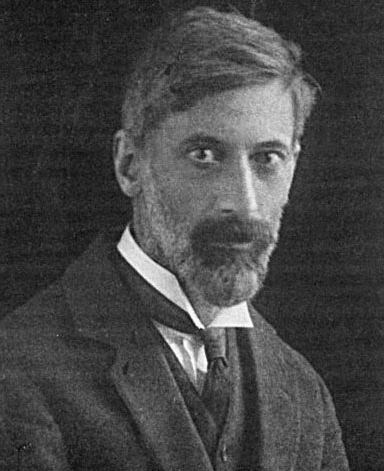

Robert W. Paul’s Early Life

Paul was born in Islington, London, in 1869. The area at the time was home to skilled workers, such as teachers, milliners and printers. It would have been an excellent place for inspiration for the Young Robert W. Paul.

After graduating from the City & Guilds Technical College, he trained at The Elliot Brothers, who made navigational, surveying and telegraph equipment for the British Admiralty. Here, Paul really owned his technical skills that led to his future success.

He later moved to the Bell Telephone Company in Antwerp.

In 1891, Paul founded his own electrical company – The Robert W. Paul Instrument Company. He settled in a workshop and office space at 44 Hatton Garden, an affluent area of London often associated with Jewellery makers and other expensive trade items.

Creating Cameras

In 1894, two businessmen approached Paul with a proposition: Create a knockoff version of Edison’s Kinetoscope.

In 1890, Edison had unveiled his Kinetoscope – a device which could show moving images to an individual viewer. The device was a massive success in the US and began to pave the way for the film industry.

However, Edison’s mafia-like grip on the film industry meant that anyone who wanted to show films had to pay extortionate royalties and rental fees. Plus, only movies made specifically for the invention could be shown. So those who wanted to make quick money created bootleg versions of the cameras or invented their own.

While Robert R. Paul initially turned down the project, he quickly realised that Edison had neglected to patent the camera in the UK or Europe.

He then purchased his own Kinetoscope and set about making a version to sell across the UK and France. He eventually made around 60 cameras which were sold to many filmmakers, including French film pioneer Georges Méliès.

As the films that could be played on the Kintescopes were under tightly controlled distribution by the Edison company, Paul needed a way to make films that could be shown on the version of the Kinetoscopes he was making and selling.

Robert W. Paul Meets Birt Acres

Around this time, he met American photographer Birt Acres. Acres worked at the Elliott and Son’s Photographic decision, so had an in-depth knowledge of the photographic process. Acres had been working on his own invention, which helped rapid photographic printing.

Together, they used their technologies to create the UK’s first 35mm camera, which launched in March 1895. Paul and Acres made “Cricketer Jumping Over Garden Gate” to test their creations. The film did exactly what it said on the tin. A man, Henry Short, jumped over a fence while dressed in cricket whites. The film, however, was never shown commercially.

Acres then directed “Incident at Clovelly Cottage” in 1895. The film showed his wife and child, alongside Henry Short in his Cricket Whites. The film became the first successful British film.

Unfortunately, The “Incident at Clovelly Cottage” is a lost film, though some frames did survive. Positive frames can be seen in two British museums – The Kodak Collection in Bradford and the Barnes Collection in St Ives.

The next Paul/Acres film was the “Oxford and Cambridge Boat Race”, shot in 1895. The film captures the annual race between the two famous universities. The film screened at Cardiff Town Hall, marking the first time a film had been shown in the UK outside of London.

After a showing of their contraption at Earls Court Exhibition Centre, Paul began to explore the idea of projecting moving images onto a screen.

However, Robert W. Paul and Birt Acres fell out and went their separate ways. It’s often said that Paul was furious that Acres had patented the camera under his own name.

Both Paul and Acres remained in the film industry as competitors.

Life After Acres

Robert W. Paul later went on to create the Theatrograph, an early type cinema projector, which he demonstrated at Finsbury College, London. His demonstration happened on the same day as The Lumiere Brother’s UK debut. The Theatrograph also toured the country with various vaudeville acts and in music halls, which helped raise the profile of movies in the UK. This, along with his cameras, made him an incredibly rich man in the space of a couple of years.

In June 1895, Paul attended the Epsom derby and recorded the finish. After processing the film overnight, he showed this to an audience. This is considered the first-ever news film. The film has been restored and can be viewed on the BFI player.

Showing Newsreels in cinemas, including races, royal appearances, incidences and propaganda shorts, became a popular part of cinema experiences right through to the end of the second world war and beyond.

Alongside Newsreels, Paul dabbled in Actualities too. Around July 1896, Paul shot Blackfriars Bride, which showed horse-drawn carriages and Victorian gentlemen crossing the Thames on the famous Central London bridge.

This was quickly followed by “Comic Costume Race”, which showed Music Hall Sports at Windsor Castle. The film is one of the few surviving videos of the annual events. Other actuality films followed.

Sea Cave Near Lisbon

In 1896, Paul presented a 13-second film called “A Sea Cave Near Lisbon” at Alhambra Theatre in Leicester Square. It was part of a series of 14 films called “A Tour in Spain and Portugal”.

Using a lightweight, portable camera, Robert W. Paul’s associate Henry Short (the jumping Cricketer), shot a single shot looking out of the Boca Do Inferno.

The film became a smash hit with audiences at the time. So much so that Paul included it in future exhibitions through to at least 1903 The film was notable for its artistic framing and the details on the waves which crashed with “great Violence”.

The Era described it as “one of the most beautiful realisations of the sea that we have ever witnessed.”

The Daily Telegraph called it “a picture of real beauty”.

It kickstarted the British documentary movement, which became one of the most popular genres of British Film.

The film itself is currently part of the BFI’s DVD collection.

Narrative Structure

But, Paul was also fascinated with the idea of storytelling in film. In 1895, he attempted to patent a way to create a time travel effect outlined by H.G. Wells in The Time Machine.

““The Spectators should be given the sensation of voyaging from the last epoch to the present, or the present epoch may be supposed to have been accidentally passed, and a present scene represented on the machine coming to a standstill, after which the impression of travelling forward again to the present epoch may be given, and the re-arrival notified by the representation on the screen of the place at which the exhibition is held …” Robert Paul (Source: Cook, Olive (1965). The Saturday Book Vol.25. London: Hutchinson & Company.)

Paul also created a vast amount of films, both independently and through the studio that he built in Muswell Hill, in North London.

In one of his early films, Robbery, Robert W. Paul show’s a wayfarer forced to hand over his clothes. Unusually, the film’s narrative places the viewers on the side of the villain.

He is also accredited with innovations like closeups, and jump cuts from one scene to another. His cameras also allowed him to do multiple exposures, which he used in his film Scrooge, or, Marley’s Ghost in 1901.

Other Projects

Outside of Films, Robert W. Paul invented the Unipivot Galvanometre in 1903, which were manufactured by the Cambridge Instrument Company. The device helped remove the disturbances caused by accelerations and so could be used in moving vehicles.

During World War I, Paul created many different electrical instruments for various military units and focused on creating wireless telegraphy sets through his electrical business, which he had kept going throughout his venture into the new film industry. He had factories in the UK and New York. This, coupled with leaving the movie business at the right time, made him very successful financially.

When Paul died in 1943, aged 73, he left a substantial number of shares to provide instruments of an unusual nature to aid physical research.